Explore Your Archive Week: Handwriting

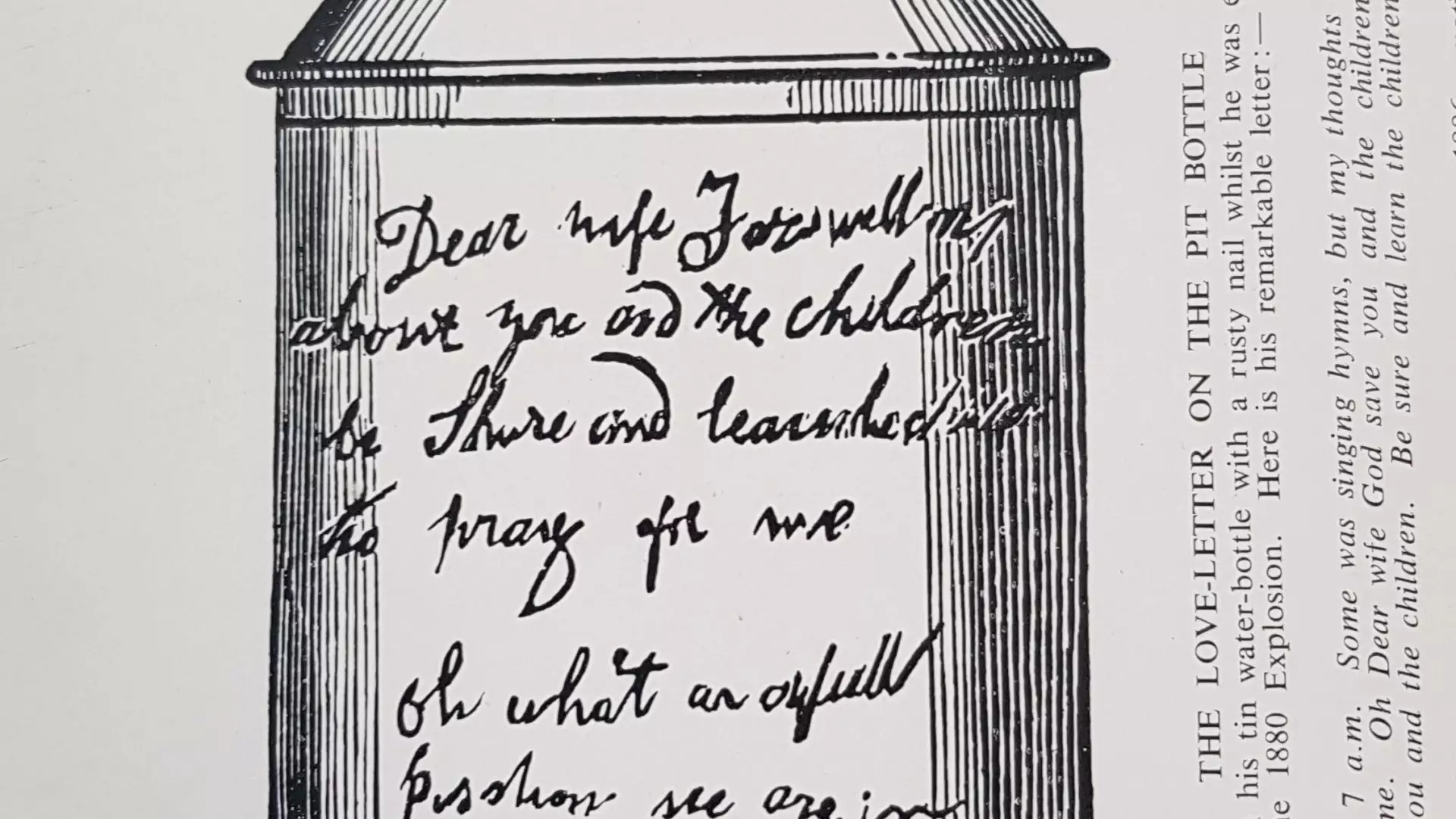

This water bottle was owned by Michael Smith, who died in the 1880 Seaham colliery disaster. Knowing he was trapped, Michael scratched a message to his wife on the side of a tin water bottle. “Dear Margaret, There was 40 of us altogether at 7am. Some was singing hymns but my thoughts was on my little Michael that him and I would meet in heaven at the same time. Oh Dear wife, God save you and the children, and pray for me…Dear wife, Farewell. My last thoughts are about you and the children. Be sure and learn the children to pray for me. Oh what an awful position we are in ! Michael Smith, 54 Henry Street”. To make matters even more tragic, Michael had left his dying infant son to go to work that day.

The explosion of Wednesday, September 8, 1880 took place at 2.20 am in the Hutton and Maudlin seams, the middle of the three levels at the pit. The highest level was the Main Coal Seam, the lowest was the Harvey. Both shafts were blocked with debris and it was twelve hours before a descent could be made. Even then the rescuers had to use the emergency kibble (an iron bucket) for the cages were of course out of action. The cage remained out of action at the Low Pit for nine days. In the pit the engine house and stables had caught fire and many of the ponies were found to have suffocated. The hooves of some of them (complete with shoes) were preserved as souvenirs, polished, inscribed and adapted to various uses, such as stands for ink-wells, snuff-boxes and pin-cushions. Fifty four ponies and a cat survived. Further on the rescuers found debris and mutilated human corpses. Body after body was then located in the dark tunnels. Nineteen survivors from the Main Coal seam were brought up the Low Pit shaft which was not blocked at the level of that seam. The main rescue work was done from the High Pit shaft where it was also possible to use a kibble. Forty eight more survivors were brought out this way. Of the 231 workers only 67 had thus been rescued by midnight of the first day, leaving 164 unaccounted for. None of these survived. Some 169 men and boys had been working in the affected seam – only 5 of these survived and were rescued.