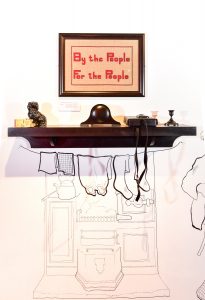

Nationalisation – By the People, For the People

The National Coal Mining Museum for England celebrates the 70th anniversary of the Nationalisation of coal.

Nationalisation is the act of taking industries out to private ownership and placing them in the hands of the government. The nationalisation of coal was an event which drew the whole industry together under the newly created National Coal Board and changed the landscape of British mining forever.

We worked with artist and illustrator Nick Elwood to create an immersive experience using his drawings to mark historic moments in the nationalisation story.

We worked with artist and illustrator Nick Elwood to create an immersive experience using his drawings to mark historic moments in the nationalisation story.

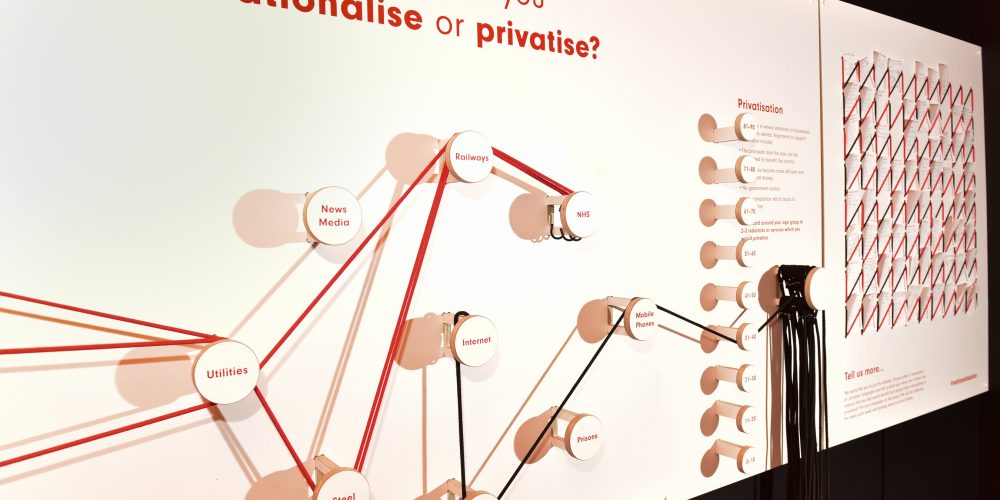

We also put the question privatisation vs nationalisation to our visitors in the debate space and asked for their opinions on this ongoing topic.

The Timeline

In 1947, Britain was going through post-war rebuilding. The specific combination of a left leaning political climate, mass unemployment and failing coal production meant plans to nationalise coal production that had been first discussed as early as 1893 were finally given the go ahead.

“the present disastrous condition of the coal industry is a direct legacy of private enterprise under which the mines were worked with an eye to quick profit rather than to any economic pattern” Somerset Herald, 8th March 1947

Described as ‘the great experiment of socialism’, over 900 pits were taken off private coal-companies’ hands and given over to public ownership by the then Labour government. All mines and collieries with over 30 miners came under the NCB, a single body which oversaw production and development, regulated wages, introduced widespread safety and welfare reforms and invested heavily in technological improvements. This shift from hundreds of individual coal companies to a single body was a task of mammoth proportions.

Described as ‘the great experiment of socialism’, over 900 pits were taken off private coal-companies’ hands and given over to public ownership by the then Labour government. All mines and collieries with over 30 miners came under the NCB, a single body which oversaw production and development, regulated wages, introduced widespread safety and welfare reforms and invested heavily in technological improvements. This shift from hundreds of individual coal companies to a single body was a task of mammoth proportions.

Date: 30 November 1945 – Miner’s Home

“They’re talking again about nationalising the pits.”

Nationalisation was viewed by many miners with both anticipation and apprehension.

Nationalisation was viewed by many miners with both anticipation and apprehension.

Those within the industry hoped it would mark the end of the coal owners’ monopoly and enable the ordinary miner’s voice to be heard. Many also believed that nationalisation would lead to better working conditions, fairer pay and improvements in living standards.

Others however, were more cautious about what changes, if any, nationalisation would bring and whether they would simply be swapping one master for another.

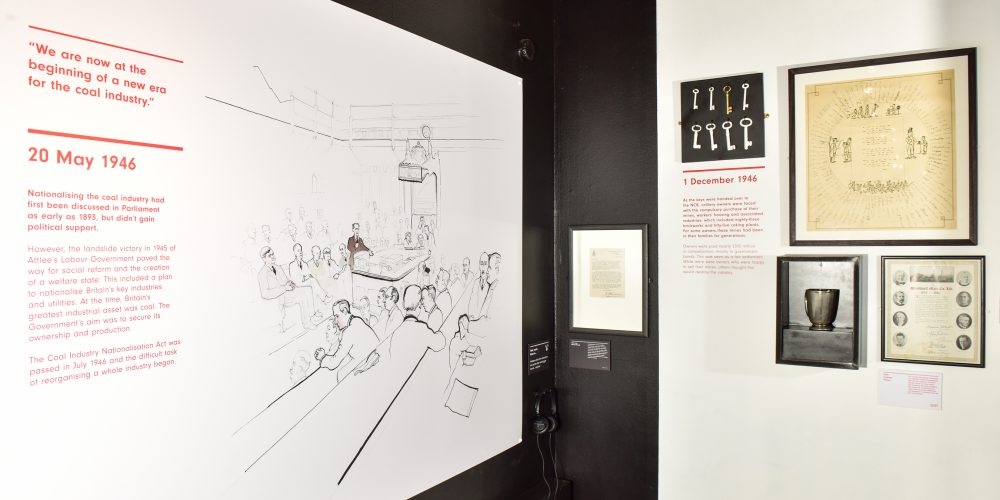

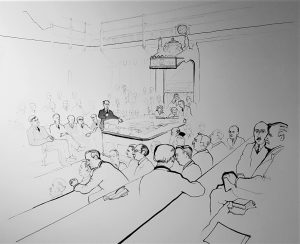

Date: 20 May 1946 – House of Commons

“We are now at the beginning of a new era for the coal industry.”

Nationalising the coal industry had first been discussed in Parliament as early as 1893, but didn’t gain political support.

However, the landslide victory in 1945 of Atlee’s Labour Government paved the way for social reform and the creation of a welfare state. This included a plan to nationalise Britain’s key industries and utilities. At the time, Britain’s greatest industrial asset was coal. The Government’s aim was to secure its ownership and production.

However, the landslide victory in 1945 of Atlee’s Labour Government paved the way for social reform and the creation of a welfare state. This included a plan to nationalise Britain’s key industries and utilities. At the time, Britain’s greatest industrial asset was coal. The Government’s aim was to secure its ownership and production.

The Coal Industry Nationalisation Act was passed in July 1946 and the difficult task of reorganising a whole industry began.

Date: 3 January 1947 – Pit Canteen

“So, what does this actually mean for us?”

Miners were concerned about the changes the NCB would bring, but initially there was little difference. Those working underground did the same job, at the same pit, under the same management.

Miners were concerned about the changes the NCB would bring, but initially there was little difference. Those working underground did the same job, at the same pit, under the same management.

Before nationalisation, there were huge differences in the structure, conditions and pay at each mine. The whole industry had to be standardised and this took time.

Eventually wages changed and most were better off. By 1950, mining was one of the highest-paid industries in Britain. The introduction of the five-day week was designed to help attract new recruits as well as improve conditions for the existing workforce.

Date: 1 December 1946 – Vesting day

“Our slogan is ‘The mines for the people – the whole of the people’.”

As the keys were handed over to the NCB, colliery owners were faced with the compulsory purchase of their mines, workers’ housing and associated industries, which included eighty-three brickworks and fifty-five coking plants. For some owners these mines had been in their families for generations.

Owners were paid nearly £310 million in compensation, mainly in government bonds. This was seen as a fair settlement. While there were owners who were happy to sell their mines, others thought this would destroy the industry.

Date: 5 January 1947 – Vesting parade

“The Coal Board is a fine team going into bat on a distinctly sticky wicket, but I think it will score a great many sixes.” Clement Atlee, Prime Minister, 1 January 1947

In a ceremony in London lasting just two seconds, ownership of Britain’s coal mines was transferred to the nation on 1 January 1947.

Alongside this formal handing over of a bound copy of the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act to Lord Hyndley, the first Chairman of the NCB, individual pits held their own Vesting Day events. Flags were flown from headgears and notices were mounted outside each pit announcing they were now “managed by the National Coal Board on behalf of the people.” A few days’ later mining communities were able to join the celebrations as parades were held across Britain.

Alongside this formal handing over of a bound copy of the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act to Lord Hyndley, the first Chairman of the NCB, individual pits held their own Vesting Day events. Flags were flown from headgears and notices were mounted outside each pit announcing they were now “managed by the National Coal Board on behalf of the people.” A few days’ later mining communities were able to join the celebrations as parades were held across Britain.

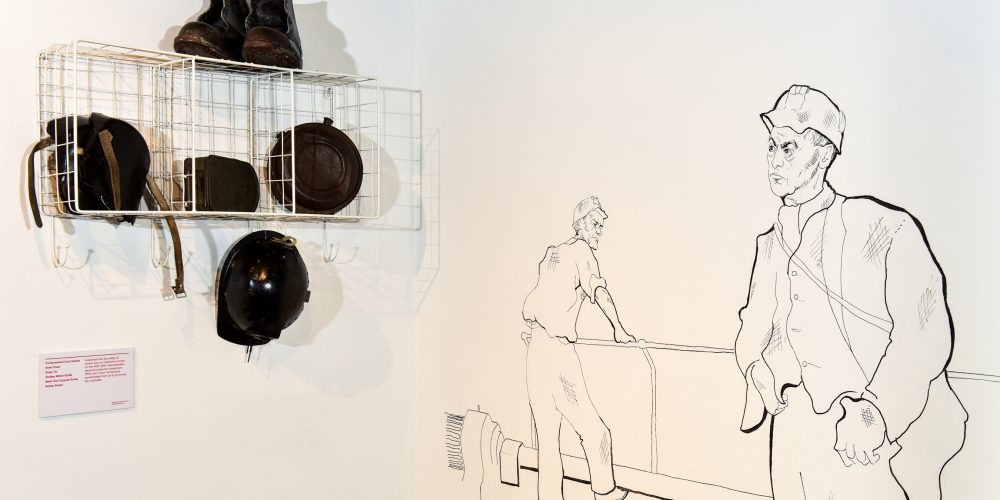

Date: 1 March 1954 – Boot room

“What do you think of these new helmets they’ve given us?”

Investment in Health and Safety was one of the NCB’s biggest priorities. The resources available, as well as its commitment to improving the safety record of mines, allowed the issues of Health and Safety to be addressed in a way that would have been impossible under private ownership.

Prior to 1947 there were just eight medical centres, but by 1960, 373 had been built. Alongside better facilities and trained medical staff, sponsored research into the problems of mining-related diseases such as Pneumoconiosis was undertaken.

Prior to 1947 there were just eight medical centres, but by 1960, 373 had been built. Alongside better facilities and trained medical staff, sponsored research into the problems of mining-related diseases such as Pneumoconiosis was undertaken.

The combination of a formal training programme and new education opportunities alongside improvements in safety equipment and provision led to the British coal industry becoming one of the safest in the world.

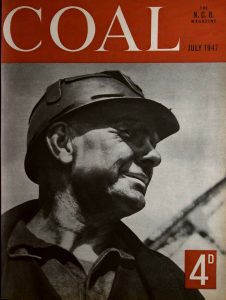

Date: 13 May 1955 – NCB Office

The National Coal Board recognised the power of branding and marketing, so with a declining workforce they focussed on recruitment.

To help change previous attitudes towards the industry, mining was rebranded as a desirable long-term career with prospects. In fact, the NCB employed the same pictorial techniques previously used in World War II propaganda material.

To help change previous attitudes towards the industry, mining was rebranded as a desirable long-term career with prospects. In fact, the NCB employed the same pictorial techniques previously used in World War II propaganda material.

Issued right across the coalfields, Coal magazine became one of the NCB’s most powerful marketing tools. Articles and artists were commissioned to promote social events, activities outside mining, and a pro-NCB feeling which started to create a sense of community throughout the regions.

For a bit of extra, click here for our Nationalisation Newsletter

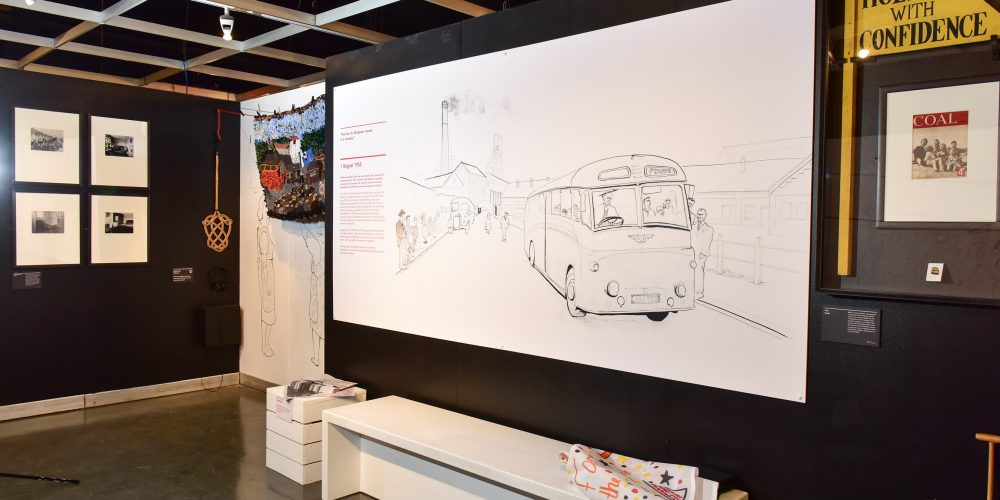

Date: 1 August 1953 – The coast

“The bus for Skegness leaves in 3 minutes!”

Welfare provision within the coal industry was already well underway before 1947; however Nationalisation radically increased and changed the range of services that were provided for, and how they were managed and funded.

From 1920 the Miners’ Welfare Fund had been providing vital social and welfare facilities for miners and their communities. From 1952 the Coal Industry Social Welfare Organisation (CISWO) was established. With representation and financial support from the NCB, CISWO continued with, and expanded the work previously undertaken by the Fund. It assumed responsibility for 700 halls and institutes, 600 recreation grounds, twenty convalescent homes and two holiday centres. A national scholarship scheme and students’ exhibition scheme was also introduced.

From 1920 the Miners’ Welfare Fund had been providing vital social and welfare facilities for miners and their communities. From 1952 the Coal Industry Social Welfare Organisation (CISWO) was established. With representation and financial support from the NCB, CISWO continued with, and expanded the work previously undertaken by the Fund. It assumed responsibility for 700 halls and institutes, 600 recreation grounds, twenty convalescent homes and two holiday centres. A national scholarship scheme and students’ exhibition scheme was also introduced.

Retiring miners also faced a better future with the introduction of one of the first occupational pension schemes for industrial workers.

Date: 7 October 1952 – Over the fence

“No more tin bath for us when we move!”

Before nationalisation few colliery owners went beyond providing the minimum standards of care for their workforce both within and outside the pit.

Before nationalisation few colliery owners went beyond providing the minimum standards of care for their workforce both within and outside the pit.

When the NCB took over, it inherited over 140,000 colliery homes, thirty-seven per cent of which were classed as ‘poor’. In order to retain and increase its workforce, the NCB recognised that improvements in social welfare needed to be made. In 1952 it set up the Coal Industry Housing Association and over the next three years built nearly 20,000 new homes.

Date: 1 January 1957 – 10 years on

“We’ve come a long way since your Dad started here.”

In 1957 the Colliery Guardian published a review of the NCB’s first ten years. Containing essays written by Coal Board members and those associated with the industry it was keen to show how far the industry had come.

What is clear to see is while the NCB brought about huge positive changes within its first decade, it was not the cure for all ills. Between 1947 and 1955 there were a record number of industrial disputes.

The reason for this is perhaps best summed up by Shinwell himself who in 1957 wrote:

“It must not be overlooked that the changeover was accompanied by two factors: the lukewarm attitude, if not the implacable hostility of the opponents of nationalisation, and the high expectations of the mineworkers . . . despite substantial improvements in working conditions, and in safety and welfare arrangements, the expectations of many of the mineworkers do not appear to have been fulfilled. “