The Hidden Lives of the Coal Traders

The Hidden Lives of the Coal Traders is about the people who made their living through the trade in coal.

Good profits could be made as coal moved from the pit to the purchaser in the great London market. Buying and selling coal was part of everyday life because it had to be, as coal powered everything from the humblest kitchen stove to the heaviest of industry, transport and even the Royal Navy.

The early coal trade relied on sea transport. Easy sea access meant that for many generations the north-east coalfield supplied London’s coal. Each stage in its journey brought extra cost, making coal in London many times dearer than at the pit top.

Canal, rail and road transport brought change, but through all its history the trade has needed regulation. From the early Coal Meters to the Approved Merchants’ Scheme, someone has had to keep an eye on three things: cost, quality and correct measure. This is still the case today for modern coal merchants.

The exhibition uses objects from the collection of the Coal Meters Committee, the Museum’s own collection and items lent by individuals. And for our younger visitors exhibits that really allow you to get your hands on history including a Reggie the Rat trail following his journey from Newcaste to London.

Click here to make a paper boat for Reggie the Rat?

From the pits in Newcastle, to the homes and industries of London, coal went through the control of many people each with a role to play and money to make.

The Lords of Coal

Hostmen: A powerful group of merchants who gained control over the nation’s coal trade from their base in Newcastle.

Hostmen: A powerful group of merchants who gained control over the nation’s coal trade from their base in Newcastle.

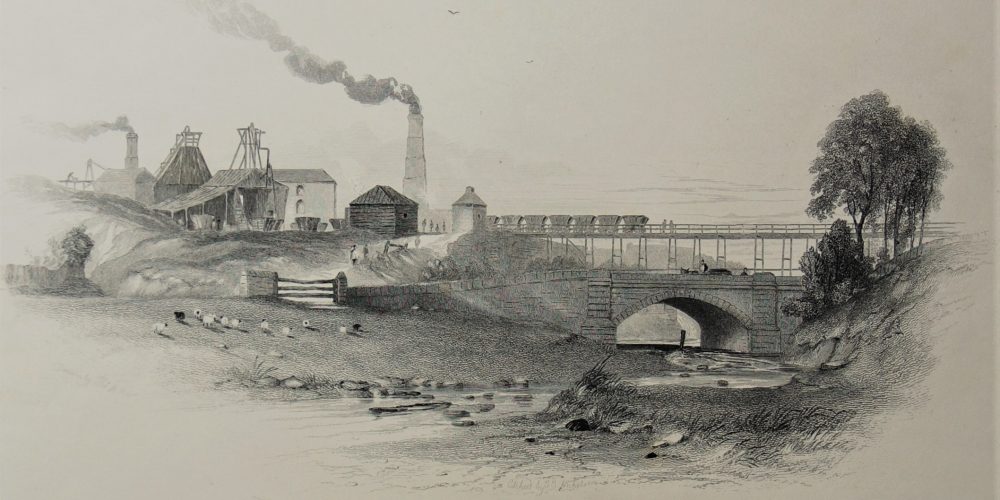

Coal is very light, so loads are bulky for their weight. The cheapest way to move it was by water. Newcastle was ideally placed for trade with London. There was plentiful coal and access along the river Tyne to the sea.

As the coal trade grew, a group of freemen called the Hostmen rose to power. These merchants began by controlling the river trade and later bought pits for themselves. Several Royal Acts aided their unique position. For more than two hundred, the Company of Hostmen could exclude any outsider from trading, governed who could sell, where and for what price.

Along the Coaly Tyne

Keelmen: Men who ferried coal in light barges, called keels, down the river Tyne to the sea-going collier ships. This was a close-knit group, often with Scottish origins.

Keelmen: Men who ferried coal in light barges, called keels, down the river Tyne to the sea-going collier ships. This was a close-knit group, often with Scottish origins.

Before canals and railways developed, wagonways and staithes sprang up along the Tyne. Staithes, or coal drops, loaded coal from chaldron wagons into keels waiting below. The sea-going collier vessels were too large to pass under Newcastle Bridge.

Keelmen signed up each year and received pay per tide, with an allowance for beer and bread. Their back-breaking work involved hand-shovelling the coal from the low keels into the much larger collier ships.

They worked for the Hostmen, who owned the keels, and their representatives, the coal fitters. Fitters were middlemen working between coal owners and ship captains. They organised transport, obtained legal documents, paid wages, custom duties and port charges.

Coal Sails

Ships’ Masters: The Master had the difficult job of sailing the coal down the east coast from Newcastle to London. The merchant captains often owned their ship.

Once the coal had been loaded, the Master bought the cargo outright, taking full financial responsibility for it. The 350 mile (560 km) voyage to London took about two weeks in good conditions. Captains could make eight to ten trips a year, with a crew of ten to twelve sailors. Between 1702 and 1813 the average ship’s capacity rose from 140 tons to 580 tons (127 – 526 tonnes).

The sea-coal trade was a risky business. Slow journeys, poor charts, storms, and privateers could all affect earnings. Trade often halted between November and February. The collier run was considered a training ground for British seamen. These sailors were much sought after by for conscription into the Royal Navy.

Weights and Measures

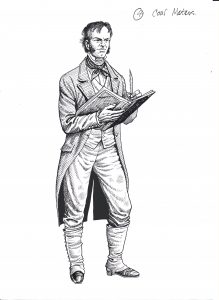

Coal Meters: Dockside officials, who measured the unloaded coals on arrival at the docks. Without a Meter present coal could not be unloaded. They kept a record of how much coal was transported and certified what the Master owed.

The ship had to register and pay the approximate import and city dues to gain an unloading warrant. Once unloaded the Coal Meter wrote the exact total on the warrant and the Ship’s Master’s bill could be settled.

A Coal Meter watched the loading of the coal into wooden measuring vats on the ship, measured by volume, and counted the vats tipped into the waiting lighter craft. Each Meter was paid meterage of 1d. per chaldron and 6 bushels (240 kg) of coal per cargo. At the wharf Land Meters measured the coal into standard sacks by weight, holding 3 bushels (120 kg). In 1800 there were fifteen Principal Meters who employed 106 Under-Meters.

Ship to Shore

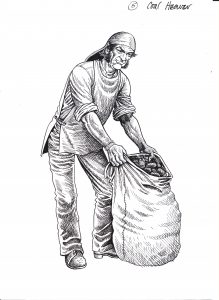

Coal Heavers: Dockside workers paid to unload coal from the ships. They were organised by Coal Undertakers, commonly publicans, who usually only employed their loyal customers.

Coal Heavers: Dockside workers paid to unload coal from the ships. They were organised by Coal Undertakers, commonly publicans, who usually only employed their loyal customers.

Coal came into London up the river Thames, a trade carried on since the fourteenth century. In 1605-6, 54,488 Newcastle chaldrons (around 145,000 tons (132,000 tonnes)) of coal were imported. By the 1660s this figure had more than trebled, and by 1700 over 460,000 tons (417,000 tonnes) reached the docks. As collier vessels became larger, they could no longer unload at the wharfs. They had to wait in the Pool, close to Billingsgate Market, for barges or lighters to carry the coal to the shore.

Coal undertakers employed coal heavers in gangs, usually nine men, who took five to seven days to unload a full cargo. When paid, they were expected to buy expensive drinks in the undertakers’ public houses if they were to be guaranteed work for the next day.

The House that Coal Built

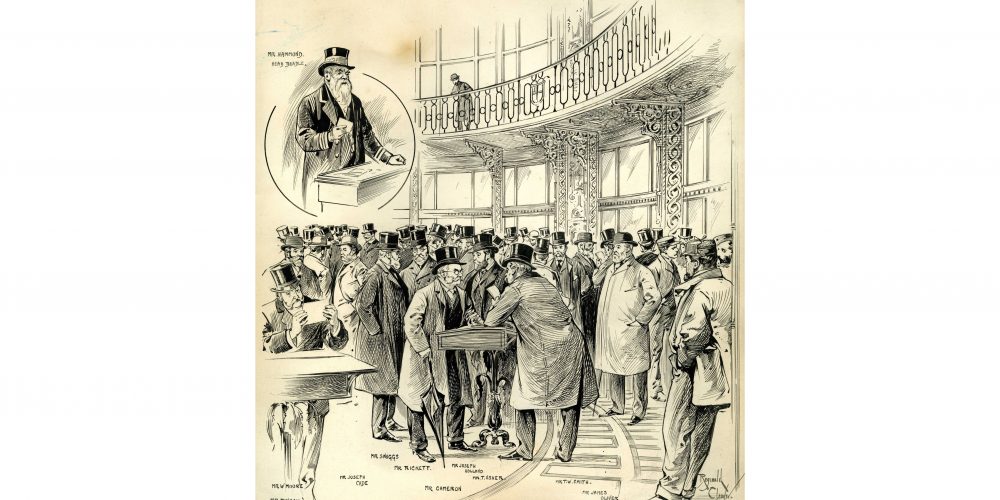

Coal Factors: Factors arranged the sale of coal at the coal market, working between Ships’ Masters and buyers. They organised warrants, legal documents and the payment of port dues.

Before 1769 factors met buyers at Billingsgate Market, a working fish market open to all. It was not an ideal place to negotiate prices. Once the factor had enough buyers for a cargo, a deal would be struck with the captain in a local pub.

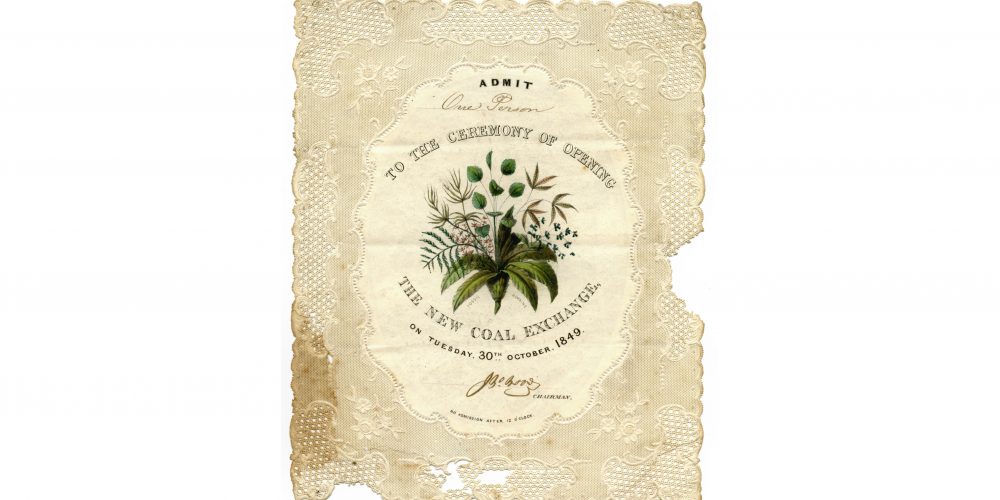

Factors and buyers combined to finance a purpose-built building. In 1769 work began on the first London Coal Exchange, replaced in 1849. Buyers had to be members to access the Exchange, with coal sales made in private rooms.

During the 1870s coal exchanges were established in other cities, including Cardiff, Hull, Leeds, Manchester, and Newcastle. Coal moved by road, canal and rail did not incur taxes, unlike sea-traded coal. Though coal still came to London by sea, earlier trade monopolies were broken.

Coal for sale!

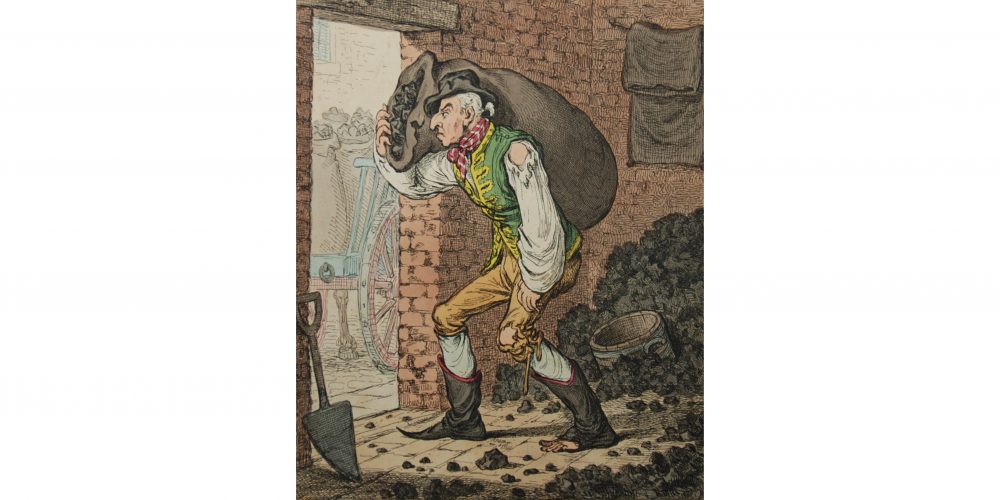

Coal Merchants: Merchants involved in the coal trade ranged across all levels of society, from members of the Coal Exchange to roving street vendors.

The first buyers in the London trade carried out their business at the Coal Exchange. They were traders with enough money and storage space to buy whole shiploads of coal. They sold to coal wholesalers, who would then sell to either large houses or individual coal sellers.

In the eighteenth century, the small coal man walked up and down the street, carrying a sack of coal, and selling small quantities to the poorer inhabitants of London. Sellers made deliveries by horse and cart, bringing coal to the door or unloading into cellars through coal holes.